Moon key data

The Moon, Earth’s sole natural satellite, constitutes a critical reference body for comparative planetology due to its well-preserved geological record and dynamically coupled evolution with Earth. Its mean geocentric distance of 384,400 km varies between363,300 km (perigee) and 405,500 km (apogee) owing to its orbital eccentricity (~0.055). These variations modulate tidal amplitudes and illuminate subtle gravitational interactions within the Earth–Moon system. With a mean diameter of 3,474.8 km*and a mass of 7.35 × 10²² kg, the Moon exhibits a bulk density of 3.34 g/cm³, indicative of a comparatively iron-poor composition. Seismological data from the Apollo Passive Seismic Experiment suggest a differentiated internal structure comprising a solid inner core (~240 km radius), a fluid outer core (~330–360 km), and a partially molten boundary layer, consistent with an early global magma ocean and subsequent chemical stratification. These interior parameters strongly support the giant impact hypothesis, wherein the proto-Earth collided with a Mars-sized impactor (Theia) approximately 4.5 Ga, producing a debris disk from which the Moon accreted.

The dynamical behavior of the Moon is equally foundational to high-precision celestial mechanics and Earth sciences. Its sidereal orbital period (27.321661 days) and synodic period (29.530589 days) differ due to Earth’s orbital motion around the Sun, while spin–orbit resonance (1:1 tidal locking) ensures that the same hemisphere remains Earth-facing. Subtle variations in orientation, known as libration, allow observation of an additional ~9% of the surface, exposing ~59% in total. Laser ranging experiments conducted with retroreflectors placed during Apollo missions provide millimeter-scale constraints on the lunar orbit, confirming the secular recession rate of ~3.8 cm/year and offering stringent tests of general relativity. The absence of a substantial atmosphere leads to extreme diurnal thermal variation, from +127°C at the subsolar point to –173°C during lunar night, resulting in large thermal stresses that drive regolith formation and affect volatile stability in permanently shadowed region

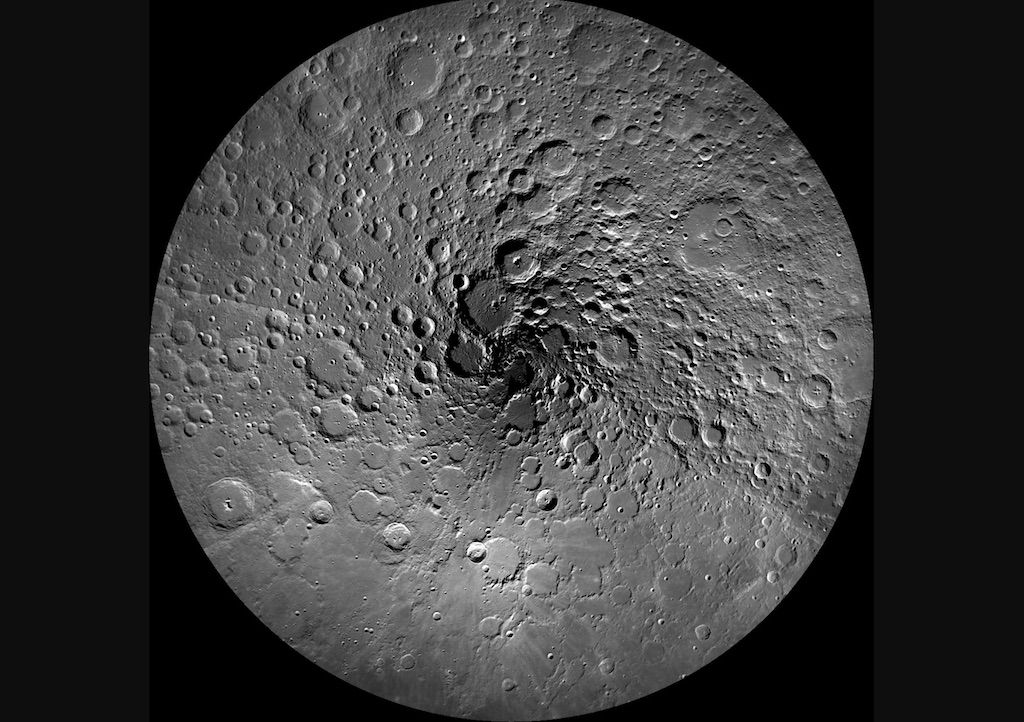

From a geological standpoint, the Moon presents a unique stratigraphic archive spanning 4.46 Ga to ~1.2 Ga, preserved due to the absence of plate tectonics and erosional processes. The dichotomy between the anorthositic, heavily cratered highlands and the mare basalts, emplaced primarily between 3.9 and 3.1 Ga, reveals early crust–mantle differentiation followed by extensive volcanic resurfacing driven by radiogenic heat. The surface is mantled by regolith layers ranging from centimeters to over 10 meters thick, generated by micrometeoroid bombardment, impact gardening, and space weathering. Spectroscopic and neutron-detector data indicate that water ice is present in cold traps near the lunar poles, particularly inside permanently shadowed craters in the south polar region, representing a resource of high strategic relevance for in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). Together, these quantitative data and geological constraints demonstrate why the Moon remains an indispensable natural laboratory for understanding planetary formation, differentiation, and long-term orbital–tidal evolution.

Moon challenges

Radiation Protection

The Moon has no magnetic field and no atmosphere, so astronauts are exposed to:

- Galactic Cosmic Rays (GCR)

- Solar particle events (SPEs)

- Secondary radiation from regolith

Long-term exposure increases cancer risk, damages the nervous system, and degrades equipment. Solutions needed:

- Regolith-covered habitats (≥2–3 m shielding)

- Buried or cave-based bases (lava tubes)

- Radiation-hard electronics and spacesuits

Extreme Temperature Swings

The lunar day lasts 14 Earth days, followed by 14 days of night, producing extreme temperatures:

- +127°C daytime

- –173°C nighttime

These conditions require:

- High-performance thermal regulation

- Nighttime energy storage (fuel cells, nuclear)

- Temperature-resistant materials and seals

Life Support and Closed-Loop Systems

For long-duration stays, the Moon must support:

- Reliable oxygen generation (electrolysis or regolith oxygen extraction)

- High-efficiency water recycling

- Controlled-environment agriculture

Apollo-style consumables cannot sustain a real base. Life support must approach near-complete recycling.

Lunar Dust Mitigation

Lunar dust is a major threat:

- Extremely sharp, abrasive particles

- Electrostatic charging makes it cling to suits and equipment

- Causes respiratory irritation if inhaled

- Can jam seals, hinges, visors, and airlocks

Solutions:

- Dust-resistant suitports (exiting through vehicle rear)

- Dust traps, electrostatic “dust wipers”

- Cleanroom-style airlocks

Reliable Energy Infrastructure

The Moon requires redundant, stable power:

- Solar power works only during the 14-day lunar day

- Nuclear reactors (Kilopower designs) needed for night survival

- Energy storage: molten salt, fuel cells, batteries

Polar regions near “peaks of eternal light” have near-continuous sunlight but require precise site selection.

Transportation and Landing Technology

To maintain a lunar base, we need:

- Heavy landers able to deliver 20–40+ tons

- Precision landing within meters, not kilometers

- Dust plume mitigation (lander exhaust excavates regolith violently)

Future bases likely need landing pads built from sintered regolith.

Habitat Construction & Pressure Management

Because the lunar surface has near-vacuum (10⁻¹² atm), habitats must be:

- Fully pressurized modules

- Resistant to micrometeoroid impacts (no atmosphere = constant bombardment)

- Expandable through in-situ materials (3D-printed regolith structures)

Local Resource Utilization (ISRU)

Long-term survival requires using local resources:

- Water ice mining at the poles

- Oxygen extraction from regolith (ilmenite reduction, molten oxide electrolysis)

- 3D-printing infrastructure from lunar soil

A sustainable base cannot depend on continuous resupply from Earth.

Long-Term Health and Physiology

Moon gravity is only 0.16 g, which is even lower than Mars. Unknown long-term effects include:

- Bone density loss

- Muscle atrophy

- Vestibular dysfunction

- Cardiovascular weakening

Countermeasures:

- Resistive exercise

- Possible centrifuge-based artificial gravity modules

Psychological and Operational Challenges

Humans must endure:

- Isolation and confinement

- Communication delays (not long, but still significant)

- Limited medical capability

- High-risk evacuation scenarios

Habitat design must support mental health, autonomy, and low crew conflict.

Lunar landing table

| Year | Mission | Country / Agency | Crew | Notes | Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Luna 2 | USSR | None | First spacecraft to reach the Moon (impact, not a landing) | ❌ No soft landing |

| 1966 | Luna 9 | USSR | None | First successful soft landing on the Moon | ✔️ |

| 1966 | Surveyor 1 | USA (NASA) | None | First U.S. soft landing | ✔️ |

| 1966 | Luna 13 | USSR | None | Returned panoramic photos | ✔️ |

| 1967 | Surveyor 3 | USA | None | Later visited by Apollo 12 | ✔️ |

| 1967 | Surveyor 5 | USA | None | Soil analysis | ✔️ |

| 1967 | Surveyor 6 | USA | None | First “hop” on lunar surface | ✔️ |

| 1968 | Surveyor 7 | USA | None | Final Surveyor lander | ✔️ |

| 1969 | Luna 15 | USSR | None | Crashed during descent | ❌ |

| 1969 | Apollo 11 | USA | Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins (orbiter) | First human landing | ✔️ |

| 1970 | Luna 16 | USSR | None | First robotic sample return | ✔️ |

| 1970 | Luna 17 | USSR | None | Delivered Lunokhod 1 rover | ✔️ |

| 1971 | Apollo 12 | USA | Conrad, Bean | Visited Surveyor 3 | ✔️ |

| 1971 | Apollo 14 | USA | Shepard, Mitchell | Precision landing | ✔️ |

| 1971 | Luna 18 | USSR | None | Crashed | ❌ |

| 1971 | Luna 20 | USSR | None | Sample return | ✔️ |

| 1972 | Apollo 15 | USA | Scott, Irwin | First Lunar Rover (LRV) | ✔️ |

| 1972 | Apollo 16 | USA | Young, Duke | Highlands exploration | ✔️ |

| 1972 | Apollo 17 | USA | Cernan, Schmitt | Last human landing | ✔️ |

| 1973 | Luna 21 | USSR | None | Delivered Lunokhod 2 | ✔️ |

| 1974 | Luna 23 | USSR | None | Hard landing, unable to drill | ❌ Partial |

| 1976 | Luna 24 | USSR | None | Last Soviet sample return | ✔️ |

| 2013 | Chang’e 3 | China (CNSA) | None | First landing since 1976; Yutu rover | ✔️ |

| 2019 | Chang’e 4 | China | None | First landing on far side; Yutu-2 rover | ✔️ |

| 2019 | Beresheet | Israel (SpaceIL) | None | Private attempt; crashed | ❌ |

| 2019 | Chandrayaan-2 Vikram | India (ISRO) | None | Crashed on descent | ❌ |

| 2020 | Chang’e 5 | China | None | Sample return | ✔️ |

| 2023 | Chandrayaan-3 | India | None | First Indian soft landing; near south pole | ✔️ |

| 2023 | Luna 25 | Russia | None | Crashed before landing | ❌ |

| 2024 | SLIM | Japan (JAXA) | None | First “precision landing”; solar power issue later fixed | ✔️ (partial success) |

| 2024 | IM-1 “Odysseus” | USA (Intuitive Machines) | None | First U.S. soft landing since 1972; private mission | ✔️ |

| 2024 | IM-2 (Nova-C) | USA | None | Attempted landing; mission failed | ❌ |

| 2025 | Chang’e 6 | China | None | Far-side sample return | ✔️ |

Artemis

More

- Eyes on the solar system (interactive lunar map)

- Far side of the Moon (wiki)

- Geology of the Moon (wiki)

- Missions to the Moon (wiki)

- NASA Moon

- Near side of the Moon (wiki)

- Space weather